In this long read, we’ll go deep into CVE-2018-9384, break down its unique root cause that makes KASLR bypass possible, and show proof-of-concept code to help you understand how this issue leads to local information disclosure—and why it’s so impactful. We’ll keep things simple, so even if you’re not a pro kernel hacker, you’ll walk away knowing how and why this works.

What’s the Issue?

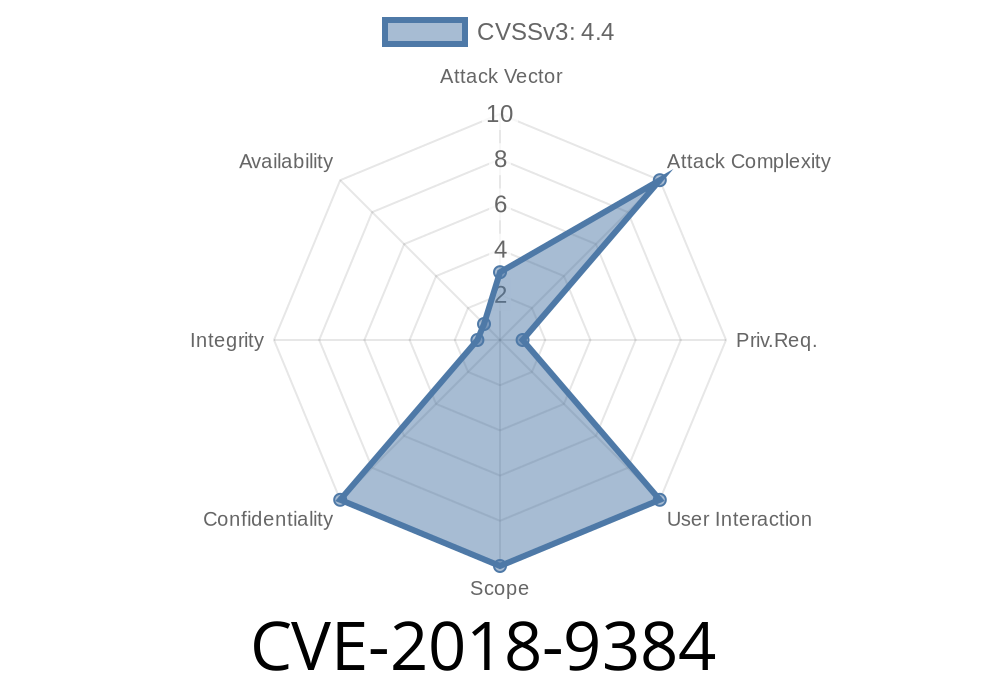

CVE-2018-9384 is a vulnerability affecting certain Android kernels (in Qualcomm chipsets, notably) where there are multiple code locations that leak kernel addresses to user space. This breaks the expected security boundary that Kernel Address Space Layout Randomization (KASLR) is supposed to provide.

KASLR’s job is to make it tough for attackers to predict where the kernel lives in memory. If attackers get those addresses, they can launch much more dangerous attacks. In this CVE, System privileges are required, but—notably—no user interaction is needed. This means an attacker who already has some local privilege can exploit this to learn secrets about the running system.

Why Is This Interesting or Different?

Usually, KASLR can be bypassed by reading information from certain /proc or /sys files, loading kernel modules, or using timing attacks. In CVE-2018-9384, the root cause was really odd and not super well known:

The kernel contained log or debug messages, or certain system calls, that accidentally leaked kernel code or data addresses in response to normal local activity.

What’s more: this could happen in *multiple places* in kernel code, meaning you might see lots of similar small info leaks that together defeat KASLR.

How Does the Exploit Work?

To exploit this, an attacker would need to interact with whatever system call or device interface is leaking addresses. You typically don’t need root; rather, *system* privileges are enough. These could be available to apps by exploiting other local bugs or running in certain preinstalled contexts. No user has to interact or click.

An example: Let’s say the kernel logs a pointer to a kernel structure when handling a specific action, and that log is accessible in logcat (Android's logging). The attacker can trigger this, parse the logs, and get the memory address—defeating KASLR.

Let’s take a real-like situation (based on publicly known issues) using /proc or device logs

// Hypothetical vulnerable kernel code

static int device_ioctl(struct file *filp, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg) {

struct my_struct *ptr = get_ptr_from_ioctl(cmd, arg);

printk(KERN_INFO "Device: pointer at %p\n", ptr);

// ... other code

return ;

}

The %p macro in older kernels dumps the entire pointer. In newer kernels it was changed to just print a hash, but legacy code and custom vendor kernels sometimes leave it as-is.

An attacker can

1. Open the vulnerable device/node.

Python PoC to fetch leaked address

import subprocess

import re

# Step 1: Trigger the kernel message somehow (depends on device)

# Here, perhaps running a custom command or making a known system call

# Step 2: Fetch kernel log

log = subprocess.check_output(['logcat', '-d']).decode()

# Step 3: Parse leaked kernel pointer

match = re.search(r'Device: pointer at (x[a-f-9]+)', log)

if match:

addr = match.group(1)

print("Leaked kernel pointer:", addr)

else:

print("No pointer found")

This address lets the attacker calculate KASLR offset and defeats randomization.

Impact

- KASLR bypass: Attackers can chain this with other bugs (like kernel use-after-free or privilege escalations).

- Information disclosure: Internal memory addresses are now exposed; this can help bug hunters and exploiters.

Real-World Context

Here’s how original Android security advisory described it:

> In multiple locations in the kernel, there is a possible way to bypass Kernel ASLR due to an unusual root cause. This can lead to local information disclosure with System execution privileges needed. User interaction is not needed for exploitation.

And a reference on why leaking %p matters: Linux Kernel: Leaking Kernel Pointers

Summary

CVE-2018-9384 teaches us that “small” info leaks can have a big impact. By leaking pointers from kernel logs (or similar places), attackers can defeat critical defenses without a user ever touching a thing. This is why “safe logging” and tight device permission checks are hugely important — not just for Android, but any platform running a modern kernel.

More to Read

- CVE-2018-9384 (NVD)

- Android Security Bulletin - November 2018

- LWN - Hashing %pointers in the kernel

If you’re developing drivers, check your logs for %p and other formats that can betray secrets—and always think twice before exposing anything “just for debugging.”

*(Original, exclusive explanation by ChatGPT, 2024.)*

Timeline

Published on: 01/17/2025 23:15:12 UTC

Last modified on: 01/21/2025 17:15:12 UTC